Design Interventions

A. Lakeside Conversations

The consultation meetings were convened by community staff and social workers in a lakeside guesthouse, a familiar setting where residents of different generations gathered. Before our intervention, the meetings usually followed a fixed “notification–discussion–decision” format. As local officials told us, this format often felt monotonous: residents spoke one by one, and the overall atmosphere remained subdued.

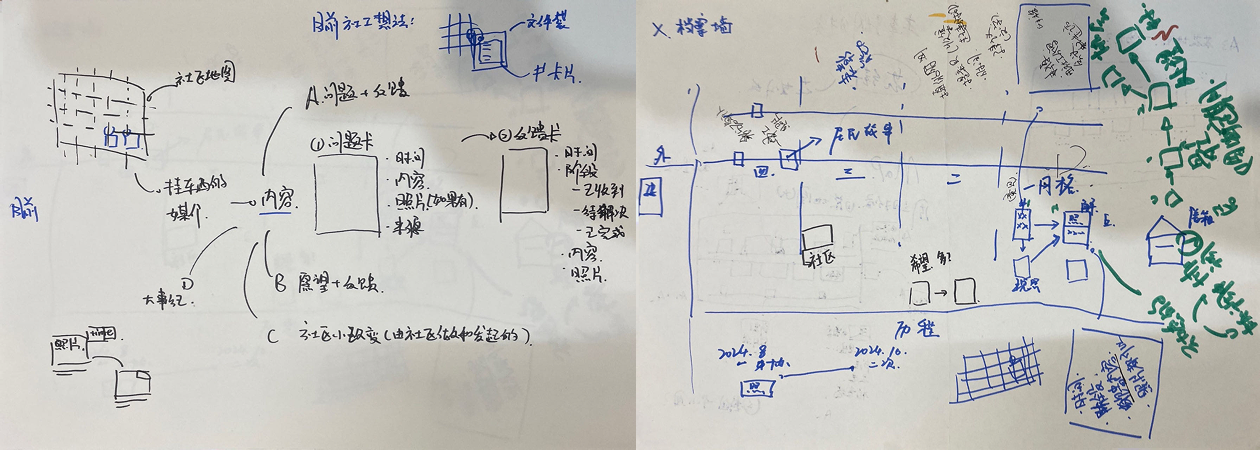

In discussions with community staff about their recent agendas and the concerns of different resident groups, we co-designed a set of participatory tools for the process. For instance, one large A0 whiteboards was prepared, with a simplified community map drawn across them. At the start of the meeting, residents placed their names and notes onto the map, indicating both their place in the neighborhood and their initial concerns. For specific agenda items—such as street waste, nighttime lighting, or the use of idle community spaces—we designed “thinking cards” with small prompts that served as trigger tools to stimulate reflection and conversation. Residents then worked in groups, using these tools to express their ideas rather than relying solely on oral discussion.

During these sessions, we observed that older participants, often silent in earlier meetings, were more willing to write down their worries or memories of past alleyway life, while younger participants proposed ways to connect current issues with longer-term goals. One elderly resident, for example, wrote about the old archway and community events once held there. This memory later resurfaced in fundraising discussions, as residents expressed a desire to contribute resources to restoring the archway.

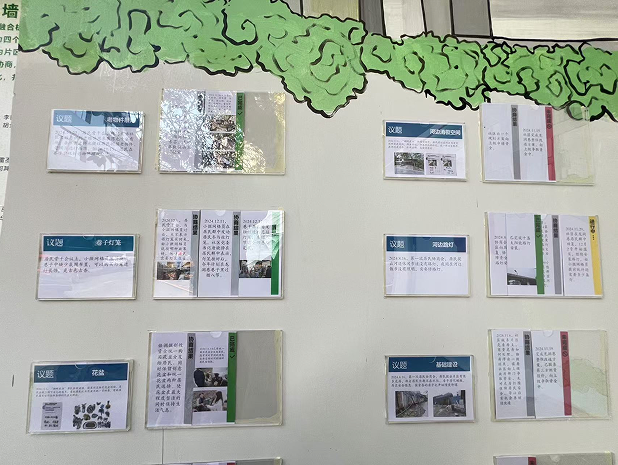

At the end of the meeting, community staff collected the cards, categorized them by theme, and translated them into actionable items Some were resolved through direct coordination, such as forming a weekend river-cleaning group. Others required collective fundraising, including the initiative to repair the old archway.

The original consultation meetings: residents sitting in rows, waiting for the social worker to call on them one by one.

Left: Residents placing stickers with their households on the prepared whiteboard map, while also noting the needs and issues around those locations.

Right: On one card asking about possible uses for an idle space, a resident suggested planting tall, long-blooming flowers such as Rosa banksiae.

Left: A resident sketching her vision of the community’s future to social worker.

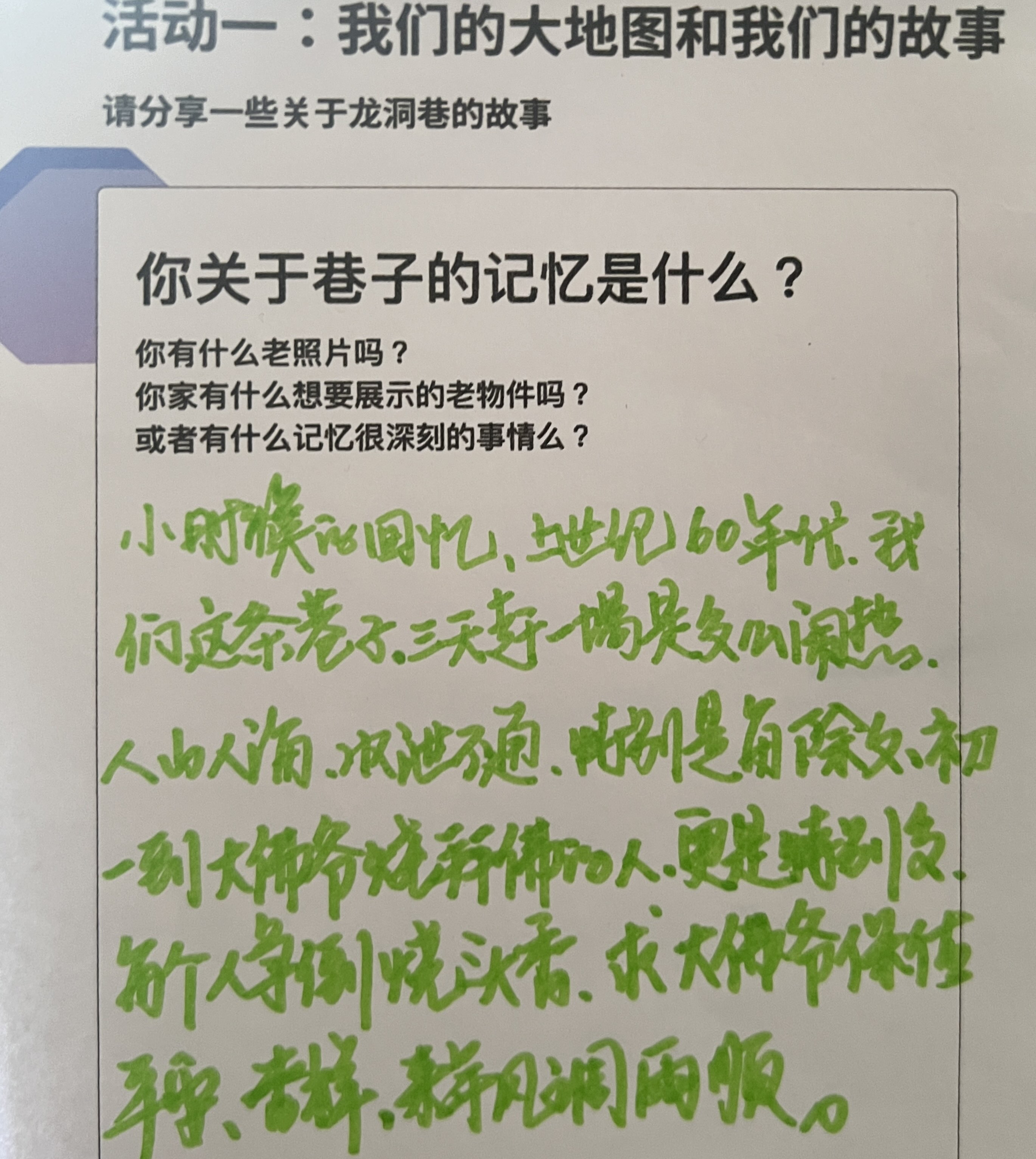

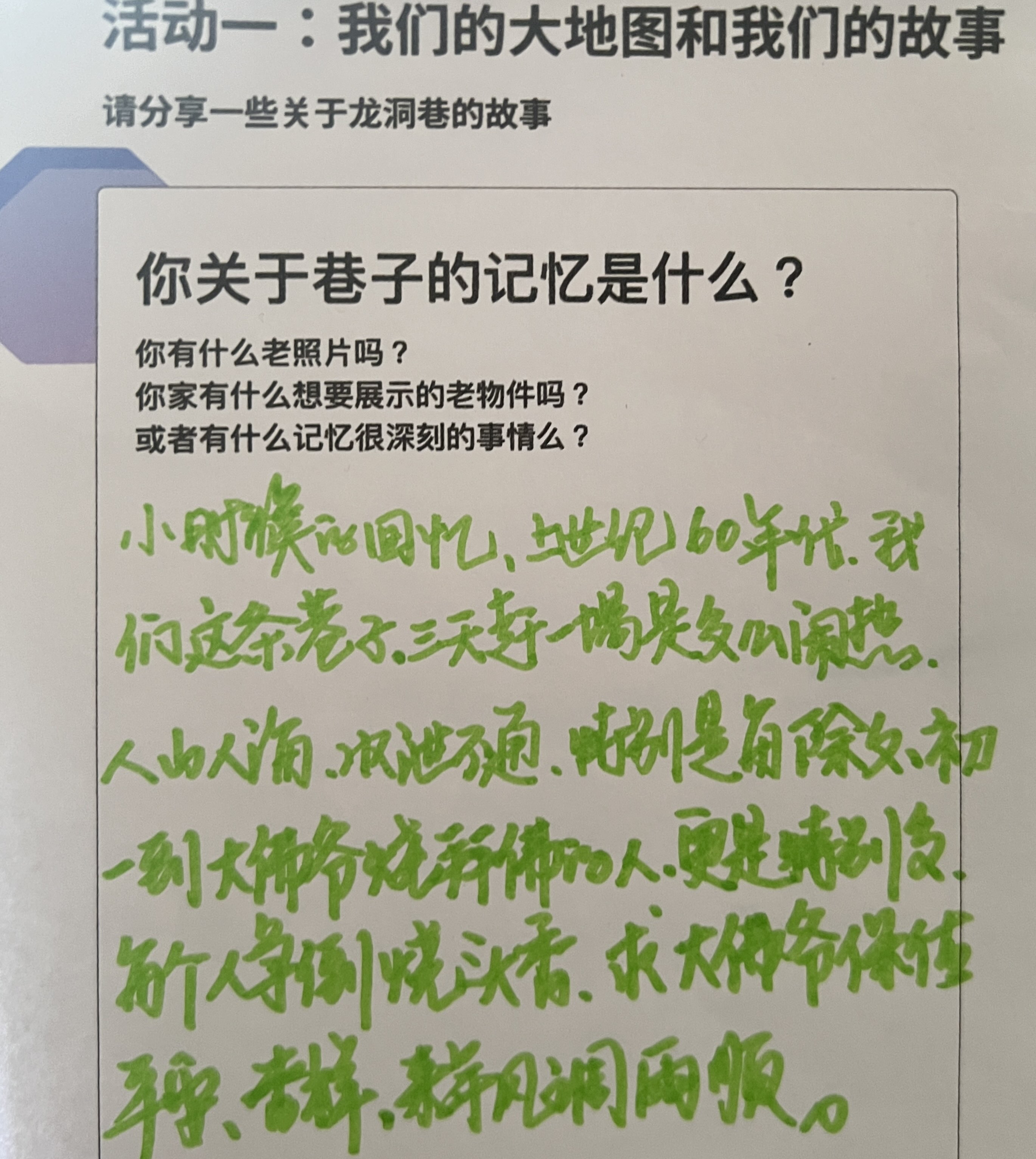

Right: A 70-year-old resident written the memories of the community in his childhood: “When I was a child, in the 1960s, this alley was crowded with people every three days for the market. It was especially lively on New Year’s Eve and the first day of the lunar year, when crowds came to the temple to burn incense. Everyone wanted to light the first stick for blessings of peace and prosperity.”

Two weeks later, during a new consultation meeting, residents initiated a fundraising effort, contributing to the community’s shared account, the first round raised RMB 10,410.

After clearing construction debris from the streets and riverbank, social workers and resident representatives purchased flowers from the community account and planted them together on the riverbank.